Assessing mental capacity

When an individual's behaviour or circumstances cast doubt as to whether they have capacity to make a decision, then a capacity assessment should be carried out in line with the Mental Capacity Act 2005.

Any capacity assessment in relation to self-neglect must be time specific and relate to a specific intervention or action; they should therefore be considered and, or repeated as risk increases and in relation to each individual risk.

When assessing the mental capacity of an adult who is self-neglecting, consider options for conducting joint mental capacity assessments, for example, involving an occupational therapist who can assist with assessing the adult’s functional ability and executive capacity. Capacity assessments must also be clearly recorded. Good practice is to record the questions as they were asked, and the responses provided by the adult.

Take a look at Appendix 2 of Norfolk SAB’s self-neglect and hoarding strategy (PDF, 1.12MB) for example screening questions to assess decisional and executive function of capacity.

Assessing capacity

Identify the decision

When assessing capacity in relation to self-neglect, the key issue to consider is whether the adult can make decisions about their circumstances and the potential risks arising from it.

Decisions about self-neglect are not always straight-forward.

Prepare for the assessment

It is helpful to think of the capacity assessment as a conversation. The decision maker needs to take all practicable steps to facilitate the conversation so that the person has the best opportunity to make the decision by themselves.

Provide the information

The professional should clearly lay out relevant information about the decision - this may include information about self-neglect and why the professional is concerned, as well as options on offer.

Test capacity

The first stage of the test should consider:

- Does the adult understand the information provided?

- Is the adult able to retain the information presented for long enough to make a decision?

- Is the adult able to use and weigh up the options? At this stage, you should also consider a person's executive function - this is particularly relevant with people who self-neglect and where risks are high or increasing.

- Can the adult communicate their decision?

If you have said no to any of the above, the second stage of the test must then consider whether the person has an impairment or disturbance of the brain.

Disturbances of the brain can be temporary including if someone is under the influence of substances.

Executive function

The MCA Code of Practice, while emphasising that an unwise decision does not of itself indicate a lack of mental capacity, recommends that capacity may need to be questioned in circumstances where repeated unwise decisions place an individual at significant risk.

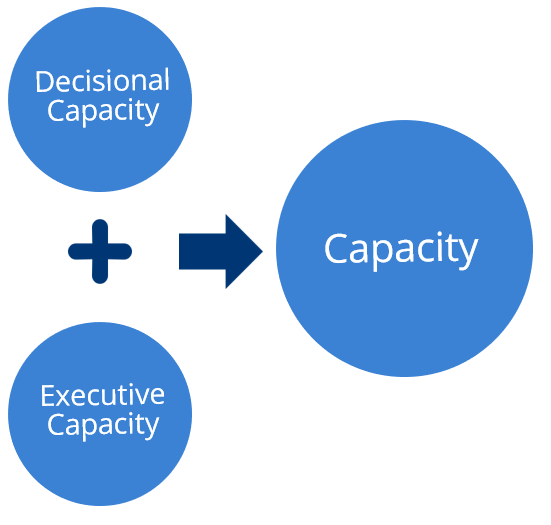

Whilst it may be determined that someone has decisional capacity around their personal welfare or their environment, this may not translate into the person's ability to carry out the actions needed to keep themselves safe or well. This may relate to a deficit in the person's executive functioning or a result of their cognitive impairment.

Impairment of executive functioning can make it difficult for a person to initiate appropriate behaviours in the moment; for example they may recognise the need to eat and drink, but fail to act on that need (Braye, Orr and Preston-Shoot, 2015). 'Articulate and demonstrate' models of assessment (tell me, then show me) can be effective in identifying if the person's executive functioning is impacting their mental capacity.

Find out more about the frontal lobe paradox, which may inform your mental capacity assessments.

Fluctuating capacity

Fluctuating capacity refers to situations where a person’s ability to make a specific decision varies. Fluctuating capacity can occur due to impact of changes in mental health (such as manic episode), physical health, dementia, an acquired brain injury or other neurological condition, the use or withdrawal of medication, or the use of illicit substances or alcohol (list not exhaustive).

The MCA code of practice indicates that a person with fluctuating capacity may be supported to make the decision (4.26). This could include supporting an individual to make a record of their views and wishes in moments where they have capacity, to help guide what course of action should be taken at the points when they do not have the capacity to make the decision(s) in question. This could include looking at risk – for example, when someone is under the influence of drugs or alcohol, how do the risks change?

If it is a one-off decision, then it may also be possible to put off the decision until the person has the capacity to make it consider timing and location of your assessment. In such circumstances, it is important to clearly record the person’s decision and why you consider that the person had capacity to make it. Other decisions need to be repeated over a period – for example, the management of a physical health condition that requires a number of ‘micro-decisions’ over the course of each day. In these circumstances, it is important to seek the views from others involved in the care and treatment of the person.

Royal Borough Greenwich v CDM provides an example of fluctuating capacity relating to micro-decisions.

What happens if the person does not have capacity

When it is determined that a person does not have capacity to make a specific decision, then a decision will need to be made in their best interests. A best interests decision should be made on their behalf, involving other professionals and anyone with an interest in the person’s welfare (such as members of the family). The less restrictive response to a person’s rights and freedoms option should always be preferred.

Where the decision is a complex one, there may be a need to involve the Court of Protection to make the best interests decision e.g. where someone lacks capacity but is objecting to the intervention or family members are in dispute.

What happens if the person does have capacity

If a person is assessed as having capacity, this should not equate to abandonment; support should be offered with reasonable adjustments to suit the persons wishes. This should involve robust risk assessment and risk management planning. We also need to consider a person’s vital interests and risks to others. In cases where the risk is high, a referral to the high-risk panel may be appropriate. There may also be cause to consider possible legal routes to mitigate risk.